The skin as a mirror: a practical guide to paraneoplastic dermatoses

Authors:

Dr. Dario Didona

Prof. Dr. Michael Hertl

Department of Dermatology and Allergology Philipps University, Marburg

Corresponding author:

Dr. Dario Didona

E-Mail: didona@med.uni-marburg.de

Vielen Dank für Ihr Interesse!

Einige Inhalte sind aufgrund rechtlicher Bestimmungen nur für registrierte Nutzer bzw. medizinisches Fachpersonal zugänglich.

Sie sind bereits registriert?

Loggen Sie sich mit Ihrem Universimed-Benutzerkonto ein:

Sie sind noch nicht registriert?

Registrieren Sie sich jetzt kostenlos auf universimed.com und erhalten Sie Zugang zu allen Artikeln, bewerten Sie Inhalte und speichern Sie interessante Beiträge in Ihrem persönlichen Bereich

zum späteren Lesen. Ihre Registrierung ist für alle Unversimed-Portale gültig. (inkl. allgemeineplus.at & med-Diplom.at)

Several systemic diseases and neoplasms can cause different skin features. Since these skin manifestations can be extremely polymorphous, dermatologists should be familiar with paraneoplastic dermatoses. Indeed, lack of familiarity with skin manifestations of internal malignancies may delay diagnosis and treatment of lethal neoplastic diseases. In this paper, we describe several paraneoplastic dermatoses, such as acanthosis nigricans, paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome, and paraneoplastic dermatomyositis.

Keypoints

-

Paraneoplastic dermatoses are classified in obligate and facultative forms.

-

More than 50 paraneoplastic dermatoses have been described in the literature.

-

Paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome is a paradigmatic example of obligate paraneoplastic dermatoses.

-

Pyoderma gangraenosum is a paradigmatic example of facultative paraneoplastic dermatoses.

Paraneoplastic dermatoses (PD) are a group of heterogeneous, acquired skin diseases, which are related to the presence of an underlying neoplasia. In 1868, von Hebra suggested that rapid alterations of cutaneous pigmentation could be associated with the presence of internal malignancies.1,2 Since the correlation between dermatological features and internal neoplasms is often not easy to identify, Curth proposed in 1976 six criteria to diagnose a PD (Tab. 1).1,2

PD and underlying neoplasm mostly develop simultaneously. However, PD can also occur before or after the detection of the neoplasia. Rarely, two PD were described in the same patient. Based on the frequency of the association between neoplasm and skin manifestation, PD are classified in obligate PD (OPD) and facultative PD (FPD). In OPD an underlying neoplasm is detected in 90–100% of the cases, whereas in FPD a neoplasia may be diagnosed in up to 30% of the cases. Since PD can be extremely polymorphous, dermatologists should be familiar with these skin manifestations to perform a correct diagnosis and eventually detect an underlying neoplasia.

Acanthosis nigricans

A paradigmatic example of FPD is acanthosis nigricans (AN). On the one hand, AN is associated with obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes mellitus, and drug intake.1,2 On the other hand, AN may be a skin manifestation of gastric adenocarcinoma (70–90% of cases), but it can be also detected in patients affected by other neoplasms, including lung and breast carcinomas.1,2 AN affects both sexes equally and is characterized by symmetrical hyperpigmentation in intertriginous areas, such as axillae, groins, neck, and submammary folds. The lesions become slowly infiltrated, with the occurrence of velvety hyperkeratotic plaques. Paraneoplastic AN should be taken into account in young adults without endocrinological alterations or genetic syndromes, who show hyperpigmentation and slowly growing hyperpigmented plaques in intertriginous areas.

Leser-Trélat sign

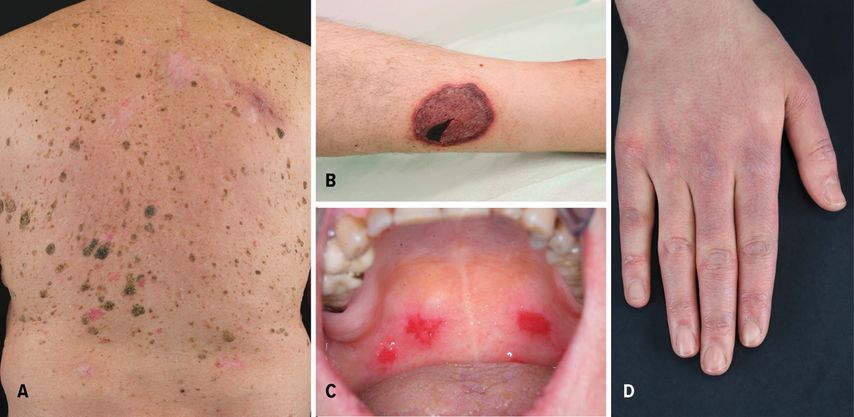

The sudden development of seborrheic keratoses in patients affected by malignancies is defined as the Leser-Trélat sign (LTS) (Fig.1A). Although Holander firstly described the association between multiple seborrheic keratoses in patients affected by internal neoplasms, nowadays the eponym LTS remains in the literature, named after Edmund Leser and Ulysse Trélat, who reported the association between eruptive angiomas and neoplasms.1,2 This association has been controversial, because seborrheic keratoses develop commonly in the elderly. However, LTS was also reported in young patients affected by osteogenic sarcoma and germinoma of the pineal body.3 About two thirds of the patients show another PD, usually AN, which was reported in approximately 30% of cases.1,2 In up to 30% of the cases, LTS is associated with gastric adenocarcinoma.1,2 In addition, LTS is frequently described in patients with lymphoproliferative malignancies (21%). Rarely, pregnancy and benign tumors may be associated with LTS.1,2

Fig. 1: (A) Sudden development of multiple seborrheic keratoses in a patient affected by gastric adenocarcinoma; (B) leg ulceration with purplish edges in a patient affected by myelodysplastic syndrome; (C) oral erosions in a patient with paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome; (D) Gottron’s papules in a patient affected by lung adenocarcinoma

Acquired pachydermatoglyphia

In 1970, Clark firstly reported acquired pachydermatoglyphia (AP), also known as tripe palm.3 It is usually associated with LTS and AN.3 Indeed, some authors consider AP as a clinical variant of AN. AP is more often reported in male patients (63%)3 and presents with yellowish, velvety, diffuse palmar hyperkeratosis that resemble intestinal villi. Gastric and lung malignancies were reported in 50% of patients with AP.3 Noteworthy, lung carcinomas were reported in more than 50% of AP patients without AN.3

Pyoderma gangrenosum

Another paradigmatic example of FPD is pyoderma gangraenosum (PG). It is a neutrophilic dermatosis, characterized by different clinical features and a variable course of the disease. PG patients usually develop painful nodules and pustules with erythematous edges. Also, PG rapidly causes deep ulcerations with undermined edges (Fig.1B), whose debridement or surgical intervention typically lead to worsening of the lesions (pathergy phenomen). Several subtypes of PG have been reported, including ulcerative, vegetating, and bullous PG. Up to 7% of PG cases are associated with an underlying neoplasia, such as myelodysplastic syndrome, myeloma, and acute myelogenous leukemia (AML).1 Bullous PG is mostly associated with underlying hematological malignancy, particularly AML.1 In addition, up to 70% of PG are associated with inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis.1 PG can be also part of several mono- or polygenetic diseases.

Paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome

Anhalt et al. first described Paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome (PAMS) in 1990.4 It is a rare autoimmune blistering disease of the skin and mucous membranes and a paradigmatic example of OPD. Nearly 84% of PAMS cases are associated with hematologic neoplasms or disorders; among these, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Castleman’s disease, and thymoma are the most frequent.4 Several auto-antibodies (auto-Abs) play a pivotal role in developing PAMS.4 Indeed, auto-Abs directed against the plakin family are typically found in PAMS, including auto-Abs against the 210kDa envoplakin, the 190kDa periplakin, the 250kDa and 210kDa desmoplakins, the 500kDa plectin, and the 230kDa bullous pemphigoid antigen.4

PAMS is characterized by polymorphous lesions, involving the skin and different mucosae. Oral erosions are usually the earliest features of PAMS (Fig.1C). Cutaneous lesions are represented by erosions, blisters, and lichenoid papules or plaques. The prognosis of PAMS is extremely poor, with a high mortality rate. Death is usually caused by severe complications, including sepsis, gastro-intestinal bleedings, and bronchiolitis obliterans.4 Prednisolone in combination with immunosuppressive adjuvants, including azathioprine (AZA), cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), or cyclophosphamide can be used as first-line therapies.4 The underlying malignancy should be treated, because it leads to improvement of the clinical features.4

Paraneoplastic dermatomyositis

Polymorphous skin features and myopathy are characteristic for dermatomyositis (DM), which belongs to the group of autoimmune myositides.5 DM is a paradigmatic example of FPD. Typical skin features are Gottron’s papules and heliotrope rash.5 Gottron’s papules present as slightly elevated, purplish lesions on an erythematous background over bony prominences, mainly on the metacarpophalangeal, interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal joints (Fig.1D). Heliotrope rash is a symmetric purplish erythema with edema involving usually the upper eyelids. Often it is associated with pruritus and can spread to the cheeks, nose, and nasolabial folds. Up to 25% of DM are associated with malignancies.5 Lung and gastrointestinal tumors have been mostly reported in DM patients.5 Immunosuppressive drugs represent the mainstay of treatment for DM, including AZA, MMF, and cyclophosphamide.5

Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet Syndrome)

Painful, edematous, shiny erythematous nodules or plaques, which usually occur on the head, neck, and upper limbs are signs of acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (AFND). AFND can be classified in to idiopathic, paraneoplastic, and drug-induced variants.1 Paraneoplastic AFND was first described by Cohen et al. in 1993.1 Skin manifestations may precede, follow, or develop simultaneously with the malignancy. Paraneoplastic AFND accounts approximately for 21% of total cases;1 85% of paraneoplastic AFND cases are associated with hematological disorders, mostly AML.1 In addition, paraneoplastic AFND can be associated with adenocarcinomas of the breast, genitourinary tract, and gastrointestinal tract.1

Conclusion

PD are important clinical hallmarks that may precede (most commonly), or occur simultaneously or after the diagnosis of a distinct neoplasm. More than 50 dermatoses are related to specific underlying neoplastic processes, many of which correlate with specific neoplasms. Recognition of the most important PD is important to establish an early diagnosis and treatment.

References:

1 Didona D et al.: Paraneoplastic dermatoses: a brief general review and an extensive analysis of paraneoplastic pemphigus and paraneoplastic dermatomyositis. Int J Mol Sci 2020; 21(6): 2178 2 Gualtieri G et al.: Detecting skin cancer: paraneoplastic skin diseases. Internist (Berl) 2020; 61(8): 860-8 3 Boyce S et al.: Paraneoplastic dermatoses. Dermatol Clin 2002; 20(3): 523-32 4 Didona D et al.: Paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome. Ital J Dermatol Venerol 2021; 156(2): 174-83 5 Didona D et al.: Paraneoplastic dermatoses. Hautarzt 2021; 72(4): 277-87

Das könnte Sie auch interessieren:

Hyperandrogenämie und „frozen ovary“

Das vermehrte Auftreten der männlichen Hormone im weiblichen Körper mit nachhaltigen klinischen Auswirkungen beginnt meist in der Pubertät, kann sich manchmal über die gesamte ...

Innovation von heute für die Medizin von morgen

Medizinischer Fortschritt rettet Leben, erhöht die Lebensqualität und verringert Leiden. Um Innovation in der Medizin weiter voranzutreiben, kooperiert die Med Uni Graz eng mit externen ...

Mitgefühlsbasierte Medizin

Das Thema Mitgefühl hat in den letzten Jahren zunehmend mehr Aufmerksamkeit im Bereich der Psychotherapie, aber auch der somatischen Medizin erhalten. Dies bezieht sich sowohl auf die ...