The Type A personality – outdated concept of a vulnerable personality trait or still alive?

Authors:

Prof. Dr. med. Karl-Heinz Ladwig1,2

PD Dr. Karoline Lukaschek3

1Klinik und Poliklinik für Psychosomatische Medizin und Psychotherapie

Klinikum rechts der Isar

Technische Universität München

2Deutsches Zentrum für Herz-Kreislauf-Forschung (DZHK)

Partnersite München

3Institut für Allgemeinmedizin

Klinikum der Universität München

LMU München

E-Mail: karl-heinz.ladwig@tum.de

Vielen Dank für Ihr Interesse!

Einige Inhalte sind aufgrund rechtlicher Bestimmungen nur für registrierte Nutzer bzw. medizinisches Fachpersonal zugänglich.

Sie sind bereits registriert?

Loggen Sie sich mit Ihrem Universimed-Benutzerkonto ein:

Sie sind noch nicht registriert?

Registrieren Sie sich jetzt kostenlos auf universimed.com und erhalten Sie Zugang zu allen Artikeln, bewerten Sie Inhalte und speichern Sie interessante Beiträge in Ihrem persönlichen Bereich

zum späteren Lesen. Ihre Registrierung ist für alle Unversimed-Portale gültig. (inkl. allgemeineplus.at & med-Diplom.at)

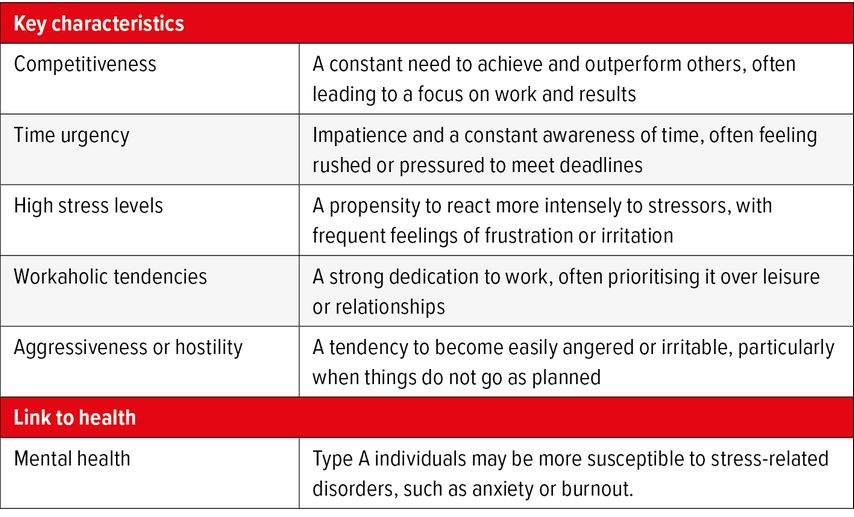

The concept of Type A personality – or Type A behaviour pattern (TABP), as it is nowadays conceptualized – originated in the 1950s as part of Friedman’s and Rosenman’s research into the relationship between behaviour and coronary heart disease. Type A individuals were characterised as competitive, ambitious, impatient, and hostile, in contrast to the more relaxed and less aggressive Type B personalities. While the construct gained significant attention in psychology and medicine for decades, its validity and utility have been increasingly questioned in contemporary research. This paper provides a narrative review of the rise and fall of the concept of Type A behaviour pattern and evaluates its subdomains.

Historical context

The genesis of Type A personality was serendipitous, and – as rumoured – originating from an upholsterer’s observation of unusual wear patterns on chairs in a cardiology practice. This anecdote, reported by Friedman and Rosenman, highlighted a behavioural peculiarity among patients – an inclination to sit at the edge of their seats, metaphorically and literally. Such behaviours inspired the pioneering studies linking Type A personality to cardiovascular outcomes.1,2 These early studies suggested a robust association between Type A personality and coronary heart disease (CHD), propelling the concept into mainstream psychological and medical discourse.

Measures of Type A personality

The operationalisation of Type A personality relied on three primary instruments, each with unique characteristics and limitations:

-

Jenkins Activity Survey (JAS) Developed in 1967, the JAS was designed to assess behavioural patterns linked to CHD.3 Its reliability coefficients ranged widely from 0.24 to 0.85, reflecting variability in consistency across different studies and samples.3,4 JAS focused on dimensions such as time urgency, competitiveness, and job involvement. However, concerns about its construct validity arose due to inconsistencies in predicting health outcomes.

-

Bortner Scale Introduced in 1969, the Bortner Scale is a self-report questionnaire that uses a continuum to evaluate traits associated with Type A behaviour pattern.5 Reliability coefficients for this scale ranged between 0.50 and 0.68.5,6 While it offered simplicity and ease of use, the scale’s moderate reliability and low intercorrelation with other Type A behaviour pattern measures raised questions about its efficacy in capturing the full spectrum of Type A behaviours.

-

Framingham Type A Scale Developed as part of the Framingham Heart Study in the 1970s, this scale focused on identifying personality traits predictive of CHD.7 Reliability coefficients for the Framingham Scale ranged from 0.54 to 0.71.7,8 Despite its foundational role in psychocardiology, the scale faced challenges due to low intercorrelations with other instruments, suggesting that it might measure distinct aspects of Type A behaviour pattern rather than the overarching construct.

Across these measures, a recurring issue was the lack of convergent validity, as intercorrelations among the JAS, Bortner Scale, and Framingham Scale rarely exceeded 0.60.6 This discrepancy indicated that each tool might capture different facets of Type A personality, complicating efforts to generalise findings.9

Besides methodological issues, the course over the lifetime deserves consideration. A study examining whether Type A behaviour contributes to CHD events included 2,394 men aged 50 to 64 years revealed clear vulnerable time windows over the course of lifetime10 Type A behaviour was assessed using the three established measures: JAS, Bortner Scale, and Framingham Scale. Follow-up examinations were conducted at 5 and 9 years to identify incident CHD cases. After 9 years, there was no increased risk of CHD associated with any of the three scores, but within a shorter observation period of 5 years, high Bortner scores were associated with increased risk of CHD events. However, over the course of 5 to 9 years the impact reversed: High JAS and Bortner scores were associated with a decreased CHD risk. Further analysis of Type A scores with regard to the time until the first CHD event found strong inverse associations for all type A scores (JAS=205: –0.49 months to first event; 95% CI:–0.20 to –0.78; p=0.001; Bortner=176: –0.27 months; 95% CI: –0.10 to –0.44; p=0.002; Framingham=0.44: –0.0011 months; 95% CI: –0.0002 to –0.0019; p=0.01).

Rise and decline of the Type A behaviour pattern

Initial studies identified Type A personality as a significant predictor of CHD and other adverse health outcomes. However, as the field matured, these findings were strongly questioned. For instance, a study measuring Type A behaviour using JAS in 516 male patients with a follow-up period of one to three years, did not find a relation between Type A behaviour and the long-term outcome of acute myocardial infarction.11 Another study examined the survival of 257 male CHD patients from the 8.5-year Western Collaborative Group Study.12 Surprisingly, over a follow-up period of 12.7 and 11.5 years, respectively, among the 231 surviving patients, Type A individuals (n=160) had a lower CHD mortality rate (19.1 per 1000 person years) than Type B individuals (n=71; 31.7 per 1000 person years; p=0,04). The survival advantage for Type A behaviour was observed across age groups and was more pronounced in those with symptomatic myocardial infarction. These findings suggest that Type A behaviour does not increase the risk of CHD mortality and may even confer some survival benefit. A large-scale meta-analysis including over 74,000 participants showed no consistent link between Type A personality and CHD,13 further challenging its status as a risk factor. Subsequent research highlighted that Type A personality’s predictive value might reside in specific subdomains, such as hostility and time urgency, rather than the broader construct.

Subdomains

Breaking down the Type A personality into its subdomains, i.e. anger/hostility, time urgency, competitiveness, speed, led to mixed results. Anger and hostility were associated with CHD outcomes both in healthy and CHD populations;14 the risk of cardiovascular events was higher in the two hours following outbursts of anger, compared to other times.15

Competitiveness and time urgency demonstrated more nuanced relationships. In the Swiss National Cohort study (n=9921) the Bortner Scale was used to collect mortality information.16 During follow-up, 3469 deaths were observed (1118 CVD deaths). The whole Bortner Scale was not associated with mortality, just the subscales competitiveness and speed: In women, competitiveness was positively associated with all-cause mortality (highest category vs. lowest: HR 1.25 [95% CI: 1.08–1.44]), CVD mortality (1.39 [1.07–1.81]), and ischemic heart disease mortality (intermediate category vs. the lowest: 1.46 [1.02–2.10]). In men, CVD mortality was inversely associated with speed (highest category vs. lowest: 0.74 [0.59–0.93]).

Population studied

In the early studies of Type A personality, the populations under investigation were predominantly male. For instance, the initial cohorts of the Framingham Heart Study, a seminal investigation in this field, included primarily male participants. This gender imbalance limited the generalisability of findings and raised questions about the applicability of Type A personality of female populations. Subsequent research sought to address this gap, but early biases in the study design have left a lasting impact on the interpretation of Type A personality-related outcomes.

Conclusion

As proposed by Rosenman and Friedman, Western society probably encourages Type A behaviour by valuing people who excel under time pressure. Consequently, Type A individuals are described as competitive, aggressive, hostile, chronically time-urgent, work-focused, and deadline-driven.

While early studies suggested that Type A behaviour pattern predicted CVD onset and progression, later research and meta-analyses failed to confirm these associations. Subsequent investigations shifted to examining TABP subdomains, such as time urgency, competitiveness, hostility, and speed, yielding partially promising findings.

Literature:

1 Friedman M, Rosenman RH: JAMA 1959; 169: 1286-96 2 Rosenman RH et al.: JAMA 1964; 189: 15-22 3 Jenkins CD et al.: J Chron Dis 1967; 20: 371-9 4 Mayes BT et al.: J Behav Med 1984; 7: 83-108 5 Bortner RW: J Chron Dis 1969; 22: 87-91 6 Edwards JR et al.: Br J Psychol 1990; 81: 315-33 7 Haynes SG et al.: Am J Epidemiol 1978; 107: 384-402 8 Lee DJ et al.: Educ Psych Meas 1987; 47: 409-23 9 Zyzanski SJ: Coronary-prone behavior pattern and coronary heart disease: Epidemiological evidence. In: Dembroski TM et al.: Coronary-prone behavior. Springer 1978; 25-40 10 Gallacher JE et al.: Psychosom Med 2003; 65: 339-46 11 Case RB et al.: . N Engl J Med 1985; 312: 737-41 12 Ragland DR, Brand RJ: N Engl J Med 1988; 318: 65-9 13 Myrtek M: Int J Cardiol 2001; 79: 245-51 14 Chida Y, Steptoe A: J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53: 936-46 15 Mostofsky E et al.: Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 1404-10 16 Lohse T et al.: Atherosclerosis 2017; 262: 19-24

Das könnte Sie auch interessieren:

Mechanische Kreislaufunterstützung im Infarkt-bedingten kardiogenen Schock

Der Infarkt-bedingte kardiogene Schock (AMI-CS) ist trotz der enormen Fortschritte in der interventionellen Versorgung des akuten Myokardinfarktes in den vergangenen Jahrzehnten ...

ESC-Guideline zur Behandlung von Herzvitien bei Erwachsenen

Kinder, die mit kongenitalen Herzvitien geboren werden, erreichen mittlerweile zu mehr 90% das Erwachsenenalter. Mit dem Update ihrer Leitlinie zum Management kongenitaler Vitien bei ...

ESC gibt umfassende Empfehlung für den Sport

Seit wenigen Tagen ist die erste Leitlinie der ESC zu den Themen Sportkardiologie und Training für Patienten mit kardiovaskulären Erkrankungen verfügbar. Sie empfiehlt Training für ...