Long bone osteomyelitis in adults: current concepts in pathophysiology and classification

Authors:

Dr. med. Marc-Antoine Burch1,2

PD Dr. med. Martin Clauss1,2

Dr. med. Rik Osinga1,3

PD Dr. med. Mario Morgenstern1,2

1 Center for Musculoskeletal Infections, University Hospital Basel

2 Department of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery, University Hospital Basel

3 Department of Plastic, Reconstructive, Aesthetic and Hand Surgery, University Hospital Basel

Corresponding author:

PD Dr. med. Mario Morgenstern

E-Mail: mario.morgenstern@usb.ch

Sie sind bereits registriert?

Loggen Sie sich mit Ihrem Universimed-Benutzerkonto ein:

Sie sind noch nicht registriert?

Registrieren Sie sich jetzt kostenlos auf universimed.com und erhalten Sie Zugang zu allen Artikeln, bewerten Sie Inhalte und speichern Sie interessante Beiträge in Ihrem persönlichen Bereich

zum späteren Lesen. Ihre Registrierung ist für alle Unversimed-Portale gültig. (inkl. allgemeineplus.at & med-Diplom.at)

Osteomyelitis is a complex infection of bone and bone marrow. The disease is complicated by the histologic and vascularization pattern of bone which prevents the penetration of antimicrobial/antifungal agents into the tissue and provides niches to microorganisms producing biofilm.1 The pathophysiology of osteomyelitis is subject of intense current research, with recent breakthrough in the understanding of survival mechanisms of various pathogens in bone tissue, in particular of Staphylococcus aureus. With respect to the pathogenesis several classification systems of osteomyelitis have been proposed in the last decades, for diagnostic and treatment guidance. We present a concise overview of the pathophysiology of osteomyelitis and considerations about two important classification systems.

Keypoints

-

Long bone osteomyelitis is a complex condition which often challenges the clinician due to ambiguous symptoms, difficult diagnosis, complex surgical management and prolonged antibiotic treatment.

-

Several classifications have been proposed to aid the clinician to correctly diagnose and treat long bone osteomyelitis.

-

The pathophysiology of long bone osteomyelitis is subject of extensive experimental and clinical research.

-

Complex cases of long bone osteomyelitis should be treated in specialized centers that provide a multidisciplinary orthoplastic and infectious-diseases approach.

Definition, etiology and epidemiology

Osteomyelitis is defined as a bacterial, fungal, or parasitic infection of bone tissue. The term is somewhat confusing, as it seems to refer to bone marrow infection only (gr. myelos: marrow), while it actually applies to all bone tissues including cortical and cancellous bone.

There are two main routes of pathogen inoculation: hematogenous and exogenous. Osteomyelitis can develop in a particular location following hematogenous spreading of a pathogen from another source, thus virtually infecting first the bone marrow and then the cortex (centrifugal infection), or being the result of direct contamination following soft-tissue disruption, either traumatic (e.g. open fracture), at end-stage of vascular insufficiency, or following surgical procedure, infecting thus first the cortices and secondarily the marrow, in a “centripetal” fashion.2

The most common pathogens involved in osteomyelitis are staphylococci (more than 70%), with specifically Staphylococcus aureus (S.aureus) being held responsible for 30–60% of all cases.3 The disease adopts typical appearances depending on the host, e.g. metaphyseal abscesses without involvement of the joint in children and adolescents, osteomyelitis of the foot skeleton in a diabetic foot syndrome or as a result of chronic occlusive peripheral arterial disease. Further, osteomyelitis can be correlated to surgical fracture treatment or joint arthroplasty and is then termed “fracture-related infection” (FRI) or “periprosthetic joint infection” (PJI).4

The epidemiologic distribution knows a bimodal age pattern, with peaks in infants <5-year-old and adults >50-year-old. Hematogenous origin is most common in children, whereas 80% of osteomyelitis cases encountered in adults are thought to originate from exogenous inoculation.5,6

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of S.aureus osteomyelitis in adults has been particularly investigated in recent years, and various survival strategies have been described that contribute to explaining the complexity of the disease and its treatment. Those includes the organization in bacterial clusters, named Staphylococcal Abscess Community (SAC), invasion of cortical canalicular network, which might promote recurrence of chronic infection, and, most importantly, biofilm formation on necrotic surface or foreign bodies. In mature biofilms bacteria are up 1000x times less susceptible to antibiotic agents and host immune response than in planktonic state. Hofstee et al. recently summarized the pathophysiology of bacterial survival strategies in bone infections in a comprehensive review article.7

Classification

A recent systematic literature review8 identified 13 published classification systems for acute or chronic osteomyelitis. The variables contained in the classifications comprise bone involvement, etiopathogenesis, soft tissue’s status or microbiology. Importantly for the treatment selection and the prognosis, some classifications also classified the disease according to the systemic status of the host. Following this review, Hotchen et al. proposed in 2019 the BACH-classification of long bone osteomyelitis.9 We present in the following the frequently used Cierny-Mader classification, issued in 1984,10 and the BACH-classification.

Cierny-Mader Classification

The Cierny-Mader system classifies osteomyelitis (acute or chronic) according to disease’s “anatomy” (localization and morphology), as well as the systemic host status, and proposes a treatment tailored to the clinical situation. The anatomic classification differentiates between medullary (Type I), superficial (Type II), localized (or full thickness) (Type III), and diffuse osteomyelitis (Type IV) (Fig.1). The physiologic classification rates the patient (the “host”) according to its clinical habitus. The scope is to evaluate the ability of the host to sustain the stress caused by the infection and the treatment, which commonly includes, beside antimicrobial treatment, debridement, osseous stabilization and bone or soft-tissue reconstruction. The patient is classified as A, B, or C-Host (Tab.1). Although microbiology and resistance profile of the involved pathogen is discussed in Cierny’s original paper, this is not considered in the Cierny-Mader Classification.10

Fig. 1: Schematic representation of the anatomic classification according to the Cierny-Mader system differentiating medullary (Type I), superficial (Type II), localized (or full thickness) (Type III), and diffuse osteomyelitis (Type IV). With permission of the AO Foundation

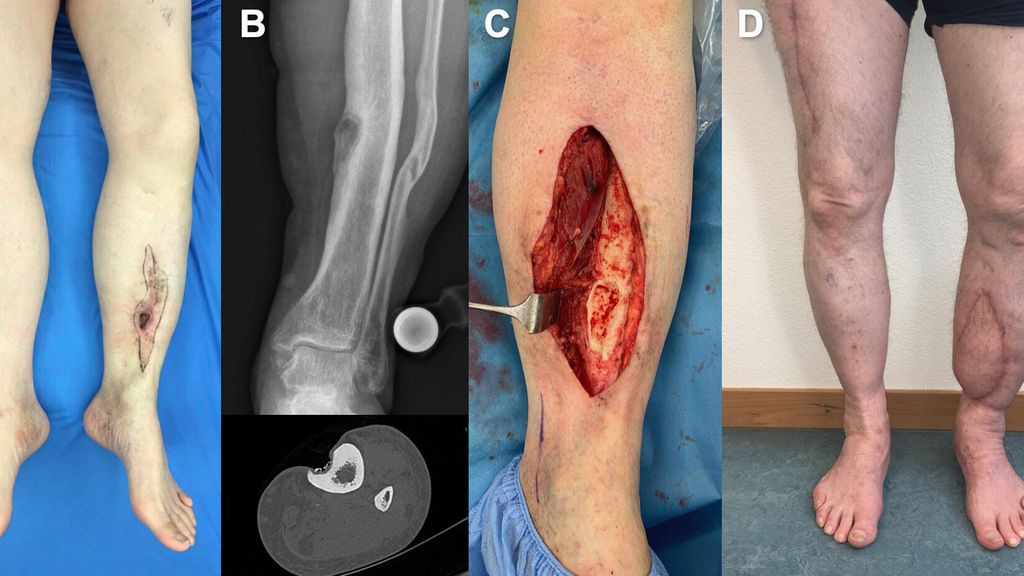

Anatomical type I osteomyelitis might be treated with intramedullary debridement, reaming and lavage. Type II osteomyelitis requires curettage and local debridement of necrotic bone tissue until vital and well perfused bone is visible (see case presentation in Fig. 2). Type III, and IV osteomyelitis require extended experience in bone and soft-tissue reconstruction. It is mandatory to perform a judicious debridement with resection of any necrotic bone or soft-tissues, since necrotic tissues are a preferred niche for pathogens. Persistence of necrotic tissues poses a significant risk factor for treatment failure with ongoing or recurrent infections. Extensive debridement is inevitably leading to bone and soft-tissue defects requiring complex multidisciplinary reconstruction strategies.11

Fig. 2: Clinical presentation of a healthy 60-year old male patient (A-Host) with a chronic fistula over the left tibia. The patient suffered an open lower leg fracture 30 years ago and is reporting a persisting fistula for 5 years (A). Corresponding radiograph and CT showing a superficial osteomyelitis overlaying a consolidated tibia fracture (B). Excision of all chronically infected cutaneous tissue and debridement of sequestra and necrotic bone tissues until vital bone with cortical bleeding is visible (C). The soft-tissue defect was reconstructed with an antero-lateral-thigh flap (from contralateral). Presentation 6 months after surgical debridement and reconstruction (D). In a superficial osteomyelitis and a consolidated fracture situation no osseous stabilization was needed. Intraoperatively collected deep tissues samples detected growth of a susceptible S. aureus and confirmed a chronic osteomyelitis in histopathological examination. The case is classified B1A1C2H1 and graded a complex osteomyelitis (Tab. 2) requiring treatment is a specialized unit

Tab. 2: Criteria of classification of osteomyelitis in the BACH system. The disease is categorized as “uncomplicated”, “complex”, or “limited options” according to the most severe assessed variable9

BACH classification

The BACH classification adapts in part the Cierny-Mader approach by considering the anatomy of the osteomyelitic lesion as well as the host status. In addition, it considers the soft-tissue coverage (overlying the osteomyelitis) and resistance profile of the involved pathogen. BACH is an acronym standing for Bone, Antimicrobial options, Coverage, and Host (Tab.2).9

The anatomic part of the classification (B – Bone) considers mainly non-segmental or segmental lesions, and further classifies lesions with joint involvement as most complex.

The BACH system accentuates on the relevance of antimicrobial efficacy against cultured pathogens at the initial evaluation of osteomyelitis (A – Antimicrobial options). Bacterial isolates are classified according to the European Society of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) criteria for stratifying pathogens into multidrug-resistant (MDR), extensively drug-resistant (XDR), and pandrug-resistant (PDR).

Soft tissues’ status (C – Coverage) is binary and assesses whether a lesion might need plastic-reconstructive expertise to eventually reconstruct a soft tissue defect. Lastly, the host status (H – Host) is classified according to actual active or controlled comorbidities, as well as the will of the patient to be treated surgically.

The disease is categorized as “uncomplicated”, “complex”, or “limited option” according to the most severely classified variable (Tab. 2). The authors recommend that any osteomyelitis patient with “complex” or “limited options” lesions should be treated by a multidisciplinary team in a specialized center.9

Conclusion

Recent advances in the understanding of osteomyelitis pathophysiology confirm the high level of complexity of the disease and have contributed to the establishment of classification systems. The central aim of these classifications is to guide treatment and patient management. The recently published BACH classification helps to identify complex cases that should be best treated in specialized multidisciplinary centers, providing early involvement of orthopaedic surgeons, plastic-reconstructive surgeons and infectious-disease specialists for tailored treatment options.

Literature:

1 Sanders J, Mauffrey C: Long bone osteomyelitis in adults: fundamental concepts and current techniques. Orthopedics 2013; 36(5): 368-75 2 Schmidt HG et al.: [Definition of the diagnosis osteomyelitis – osteomyelitis diagnosis score (ODS)]. Z Orthop Unfall 2011; 149(4): 449-60 3 Tong SY et al.: Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev 2015; 28(3): 603-61 4 Metsemakers WJ et al.: Fracture-related infection: aconsensus on definition from an international expert group. Injury 2018; 49(3): 505-10 5 Calhoun JH, Manring MM: Adult osteomyelitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2005; 19(4): 765-86 6 Lee YJ et al.: The imaging of osteomyelitis. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2016; 6(2): 184-98 7 Hofstee MI et al.: Current concepts of osteomyelitis: from pathologic mechanisms to advanced research methods. Am J Pathol 2020; 190(6): 1151-63 8 Hotchen AJ et al.: The classification of long bone osteomyelitis: a systemic review of the literature. J Bone Jt Infect 2017; 2(4): 167-74 9 Hotchen AJ et al.: The BACH classification of long bone osteomyelitis. Bone Joint Res 2019; 8(10): 459-68 10 Cierny G, Mader JT: Adult chronic osteomyelitis. Orthopedics 1984; 7(10): 1557-64 11 Metsemakers WJ et al.: Evidence-based recommendations for local antimicrobial strategies and dead space management in fracture-related infection. J Orthop Trauma 2020; 34(1): 18-29

Das könnte Sie auch interessieren:

Neueste Entwicklungen der spinalen EndoskopieNachhaltige keramische Knochenimplantate bald aus dem 3D-Drucker

Die endoskopische Wirbelsäulenchirurgie hat sich von einer rein perkutanen Technik zu einer hochpräzisen, technisch ausgereiften Methode entwickelt, die ein weites Spektrum degenerativer ...

Seltene Kleingefässvaskulitiden im Fokus

Bei Vaskulitiden der kleinen Gefässe liegt eine nekrotisierende Entzündung der Gefässwand von kleinen intraparenchymatösen Arterien, Arteriolen, Kapillaren und Venolen vor. Was gilt es ...

Elektive Hüft-TEP bei Adipositas Grad III

Übergewichtige Patient:innen leiden früher als normalgewichtige Personen an einer Hüft- oder Kniearthrose. Allerdings sieht die aktuelle S3-Leitlinie zur Behandlung der Coxarthrose in ...