Anticoagulation in Acute Pulmonary Embolism: Which Drug? How Long?

Authors:

Aria Roohi, MD1

Helia Robert-Ebadi, MD, PD1, 2

1 Division of Angiology and Hemostasis

Geneva University Hospitals

2 Faculty of Medicine, Geneva University

E-Mail: helia.robert-ebadi@hcuge.ch

Vielen Dank für Ihr Interesse!

Einige Inhalte sind aufgrund rechtlicher Bestimmungen nur für registrierte Nutzer bzw. medizinisches Fachpersonal zugänglich.

Sie sind bereits registriert?

Loggen Sie sich mit Ihrem Universimed-Benutzerkonto ein:

Sie sind noch nicht registriert?

Registrieren Sie sich jetzt kostenlos auf universimed.com und erhalten Sie Zugang zu allen Artikeln, bewerten Sie Inhalte und speichern Sie interessante Beiträge in Ihrem persönlichen Bereich

zum späteren Lesen. Ihre Registrierung ist für alle Unversimed-Portale gültig. (inkl. allgemeineplus.at & med-Diplom.at)

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a frequent disease with significant morbidity and mortality if not properly treated. During the last decade, many important advances have been achieved in the anticoagulant treatment of patients with PE. In particular, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have largely replaced vitamin K antagonists (VKA), not only in the treatment of the acute PE episode, but also in the long-term prevention of PE recurrence.

Keypoints

-

DOACs are currently the first-choice anticoagulant treatment in patients with acute stable PE.

-

They are associated with similar efficacy to vitamin K antagonists in terms of reducing venous thromboembolic events during treatment, with a better safety profile and reduction in major bleeding events.

-

Recurrence risk assessment after acute PE has evolved from a binary provoked/unprovoked classification towards a more refined definition including major/minor risk factors and consideration of the transient/persistent character of risk factors.

-

The possibility of a prescribing low dose DOACs for secondary prevention of VTE recurrence after a first episode of PE has considerably improved the benefit-risk ratio of long-term anticoagulation in this setting.

Historical Evolution of Anticoagulation in Acute Pulmonary Embolism

The first randomized trial in the field of anticoagulant therapy in patients with acute pulmonary embolism (PE) was conducted about 60 years ago. In comparison with no treatment, heparin resulted in dramatic decrease in PE-related death and non-fatal recurrences.1

Over the last six decades, major advances have occurred in the treatment of acute PE. First of all regarding the available drugs: from nothing to intravenous (IV) unfractionated heparin (UFH) followed by oral vitamin K antagonists (VKA), subcutaneous (SC) low molecular weight heparins (LMWH) and fondaparinux have then gradually replaced the initial IV UFH, and finally the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) which have completely changed the management of patient with acute PE for the last decade. The second major evolution is the treatment setting: whereas hospital admission and strict bed rest was the rule for all patients with acute PE but also acute deep vein thrombosis (DVT), early mobilization and outpatient treatment is now the standard of care for almost all patients with DVT and a large proportion of patients with acute PE. Finally, in the field of long-term prevention of venous thromboembolic (VTE) recurrence, risk stratification tools have been developed and the efficacy of low-dose DOACs was demonstrated. These progresses altogether have led to a complete change in the paradigm of management of patients with acute venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Which Anticoagulant Drug to Use in Acute PE?

The anticoagulant molecules currently available on the market in 2022 include UFH, LMWH, fondaparinux, VKA, and DOACs. Unlike the parenteral UFH, LMWH, and fondaparinux which need to bind to antithrombin in order to exert their anticoagulant activity, DOACs directly and selectively inhibit one activated coagulation factor: factor Xa for rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban, and factor IIa (thrombin) for dabigatran.

The traditional scheme in patients with acute PE has long been to initiate treatment with a parenteral drug (UFH, LMWH or fondaparinux) overlapped and followed by a VKA. The aim of this overlap period of at least five days is to achieve immediate therapeutic anticoagulation while allowing time for the VKA to reach stable anticoagulation. Pragmatically, this is defined by the achievement of two INR in the target therapeutic range of 2.0 to 3.0 on two consecutive days, before stopping the parenteral drug.2

The introduction of DOACs represented a revolution by considerably changing the ease of management of anticoagulation initiation, as will be discussed in more detail below, and has contributed to increase the possibility of outpatient management of many patients.

DOACs: General Information

The four DOACs admitted by Swissmedic as of 2022, in chronological order of the availability on the Swiss market, consist of one thrombin inhibitor: dabigatran (Pradaxa®); and three Xa inhibitors: rivaroxaban (Xarelto®), apixaban (Eliquis®), and edoxaban (Lixiana®).

A detailed discussion of the DOACs’ pharmacokinetics is beyond the scope of this paper. The important notions are that all these drugs achieve a rapid peak concentration after oral ingestion (around 2 hours) and have a similar half-life (around 10–12 hours). In terms of metabolism, rivaroxaban and apixaban are metabolized mainly via the CYP3A4 whereas this pathway is minimally involved for edoxaban. In terms of renal excretion, a simple message to bear in mind is that dabigatran is largely eliminated by renal excretion (>80%) whereas for the Xabans there is approximately 40% renal excretion of the absorbed dose in the unchanged form.3

DOACs: Phase III VTE Trials

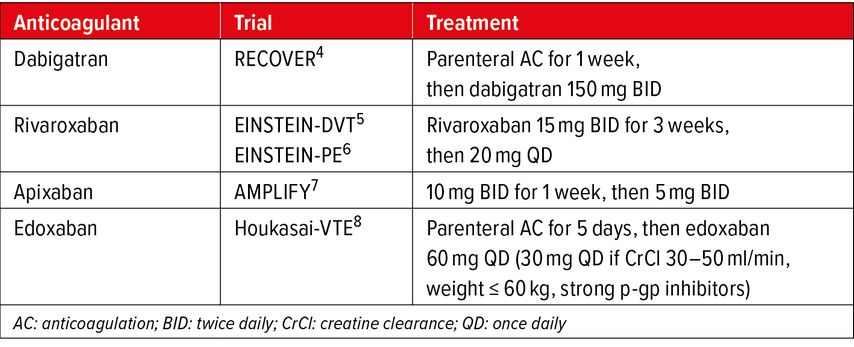

The phase III randomized controlled trials of DOACs in the setting of VTE were designed as non-inferiority trials compared to standard treatment with LMWH/VKA and are presented in Table 1.

Exclusion criteria in these trials to consider for prescription in daily practice are:

-

severe renal impairment, most often defined by a creatinine clearance according to the Cockroft-Gault formula <30ml/min/1.73m2 and

-

liver dysfunction, with a more variable definition across studies, including any hepatic impairment, significant liver cirrhosis CHILD A or CHILD B, or an increase in liver function tests AST/ALT more than twice upper limit of the normal range.4–8

Regarding the primary efficacy outcome of VTE recurrence risk, the pre-specified non-inferiority criteria was met in all these studies. The safety outcome of major bleeding risk was lower on DOACs compared to standard treatment, reaching statistical significance in the rivaroxaban PE and apixaban studies.6,7 A meta-analysis of Xa inhibitors’ studies on efficacy and safety issues shows significantly lower risk of major bleeding, intracranial bleeding – which is often the most feared bleeding complication – and of fatal bleeding on DOACs compared to VKA.9

In terms of bleeding patterns, it is interesting to observe that the risk of major gastrointestinal (GI) bleedings was higher on most DOACs (rivaroxaban, edoxaban, dabigatran) compared to VKA, with the exception of apixaban.4–9 This observation was consistently reported in phase III trials but also in post-marketing studies and real-life data. Abnormal uterine bleedings in women of child bearing age have also been reported to be twice as frequent on rivaroxaban compared to VKA, but not on apixaban. These important information on bleeding patterns should be kept in mind when choosing a DOAC in a given patient.

Anticoagulant Treatment in Acute PE: Initiation Phase and Maintenance Phase

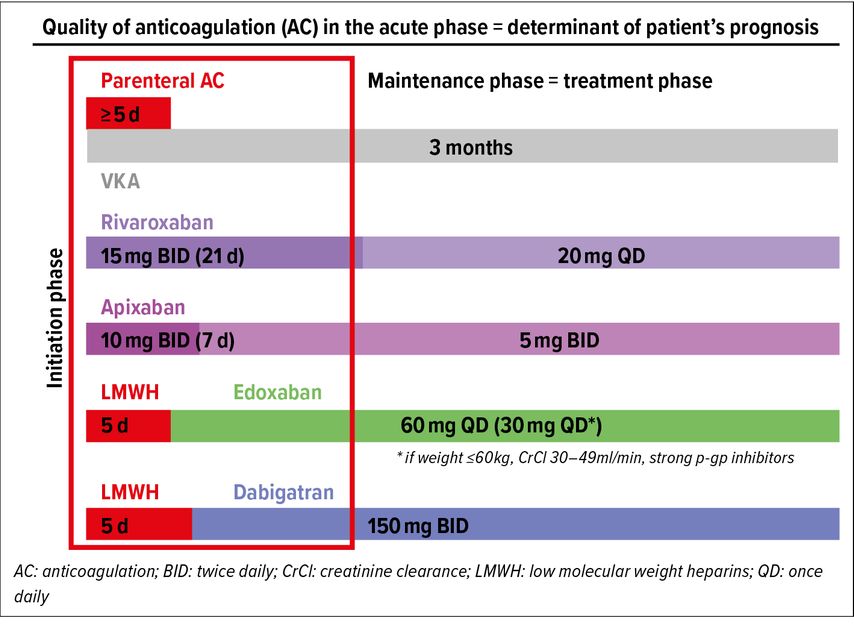

The quality of anticoagulation in the acute phase is a major determinant of patient’s prognosis. Across phase III trials, the pharmaceutical companies adopted two different strategies to address this issue: 1) starting with a lead-in phase of 5–7 days of SC LMWH followed by oral DOAC maintenance dose (edoxaban, dabigatran),4,8 or 2) starting directly with oral DOAC at high-intensity dose (21 days for rivaroxaban, 7 days for apixaban) before moving on to maintenance dose.5–7

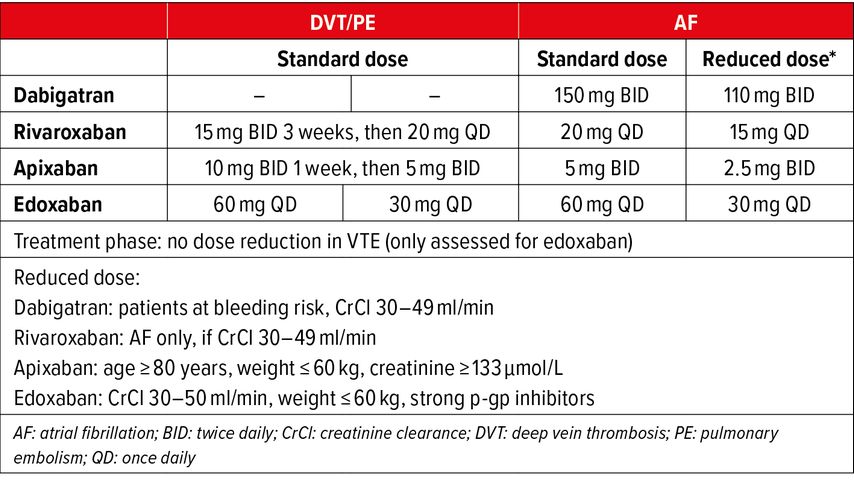

All options of anticoagulation schemes and dosing regimens for the initiation phase and the maintenance (also called treatment) phase are illustrated in Figure1. Complying with these proven schemes and regimens is important in order to insure treatment efficacy. It should also be emphasized that these dosing regimens differ from dosing regimens of atrial fibrillation (AF) trials, where there is no distinction between initiation phase and maintenance phase. Moreover, for maintenance (treatment) phase, as opposed to AF, reduced doses have not been assessed in VTE trials with the exception of edoxaban with defined criteria (see Tab. 2). In view of all the favorable results of DOAC trials and their ease of use, DOACs have now become the first-choice anticoagulant treatment in acute VTE.10,11

Fig. 1: Anticoagulant treatment initiation in acute PE. Two different strategies: LMWH or high-intensity DOAC

A practical guide for prescription of DOACs in clinical practice including all dosing regimens can be found on the Angiology and Hemostasis website at the following link: https://www.hug.ch/sites/interhug/files/structures/angiologie_et_hemostase/documents/a65_acods2019_4.pdf .

Duration of Anticoagulation After Acute PE

In order to answer the question of “how long” we should treat patients after an acute episode of PE, we first have to discuss how the risk of recurrence after treatment cessation can be assessed. One of the main determinants of recurrence risk consists of the circumstances in which the initial PE occurred.

Circumstances of Initial PE

Recurrence risk varies widely depending on the context of the index PE episode. It has long been known that if PE occurs in a post-operative setting (“provoked PE”), the risk of recurrence after stopping treatment is very low.12 On the other hand, if there is no identified risk factor (“unprovoked PE” also referred to as “idiopathic PE”), the risk of recurrence after treatment cessation is as high as 10% at one year.12 In between these scenarios are all PE episodes provoked by one or several non-surgical risk factors, in which recurrence risk after anticoagulation cessation remains quite high.12

There has been longstanding and still ongoing debate on what defines an unprovoked or idiopathic VTE. In 2016, the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) suggested that VTE can be considered idiopathic when it is not provoked by transient risk factors (surgery, trauma, hospitalization, and prolonged bed rest for at least 72 hours in the past 3 months) and if there is no persistent risk factor, active cancer or chronic inflammatory disease.13 More recently, oral oestro-progestative contraception and pregnancy were added as important transient risk factors, based on data showing a low recurrence risk after hormonal exposure ceases. Gradually, it has been acknowledged that VTE risk factors are more of a continuous spectrum, and that a binary separation between provoked and unprovoked VTE is a reductive representation of clinical reality.10

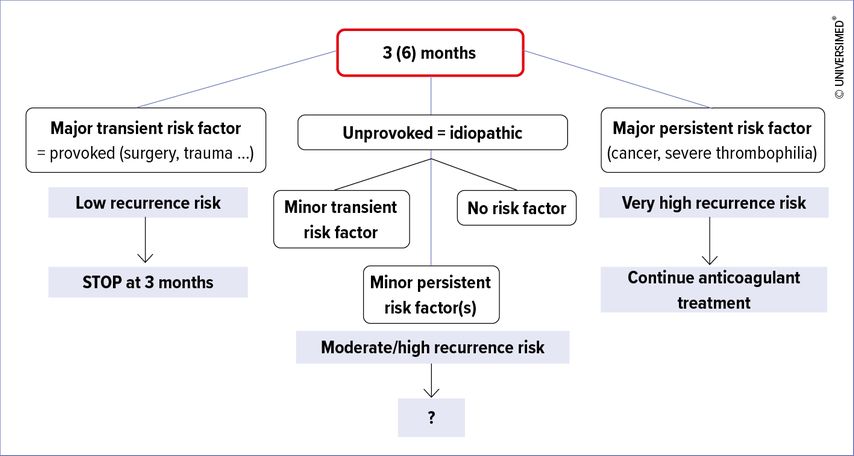

In clinical practice, patients are often assessed at 3 to 6 months of anticoagulant treatment. At this time point, several scenarios are possible (see Fig. 2). In patients with a PE provoked by a major transient risk factor, anticoagulation is stopped. On the other side of the spectrum, in case of active cancer or severe thrombophilia, the high recurrence risk justifies long-term treatment. The middle group – the most challenging – is represented by a spectrum of patients with minor transient risk factors, minor persistent risk factors, or no risk factors at all, who have a moderate to high recurrence risk. In these, an individualized decision is necessary, taking into account the bleeding risk and the benefit-risk ratio as well as patient’s preferences, which are sometimes strongly and clearly expressed.

Assessing the Risk of Recurrence

To date, the only rule which has proven to be efficient in a prospective validation study is the HERDOO2 rule.14 The full name of the rule is «men continue and HERDOO2». What we know from epidemiological studies is that men recur twice as often as women after stopping treatment in case of an idiopathic VTE. Basically, HERDOO2 contains items based on the presence of lower limb post-thrombotic syndrome, D-dimer measurement >250µg/L on anticoagulant treatment, the presence of obesity with a BMI ≥30kg/m2, and age >65years.14 The aim of this rule is to identify women at low risk of recurrent VTE (<3%) who can stop anticoagulant treatment.

How Long Anticoagulant Treatment Should be Continued?

The earlier studies comparing 3 months of anticoagulation versus continued treatment,15 or 3 months versus 12 months,16 after a first episode of idiopathic VTE, showed that recurrence risk remained low as long as treatment was pursued. Nevertheless, prolonging treatment duration for the first episode did not have any impact on recurrence risk after treatment cessation, so that the long-term recurrence risk remained unchanged, as confirmed once again in a more recent randomized trial.17 The ESC guidelines and CHEST guidelines stated a preference, after a first episode of unprovoked PE, to extend anticoagulation without scheduled termination date over a limited period of 3 months, provided the patient is at low (to moderate) bleeding risk.10,11,18,19

What Dosing Regimen Should be Chosen for Long-Term Prevention of VTE Recurrence?

The available evidence on secondary prevention mainly arises from two studies: the AMPLIFY EXTENSION study demonstrated non-inferiority of a reduced dose of apixaban 2,5mg BID compared to therapeutic dose of 5mg BID.20 The second study is the EINSTEIN-CHOICE study, which included patients with confirmed symptomatic DVT and/or PE who completed 6–12 months of anticoagulant treatment and were randomised to receive aspirin (100mg QD), rivaroxaban 10mg QD or rivaroxaban 20mg QD. This study showed superiority of both doses of rivaroxaban compared to aspirin, and no difference in the recurrence risk with rivaroxaban 10mg compared to rivaroxaban 20mg.21

The latest ESC guidelines state that a reduced dose of apixaban or rivaroxaban should be considered after 6 months of therapeutic anticoagulation if long-term oral anticoagulation is decided after PE in patients without cancer.10

Conclusion

In conclusion, DOACs are currently the first-choice anticoagulant treatment in patients with acute stable PE. Recurrence-risk assessment after acute PE has evolved from a binary provoked/unprovoked classification towards a more refined definition including major/minor risk factors and consideration of the transient/persistent character of risk factors. Finally, the possibility of a dose reduction has considerably changed the benefit-risk ratio of long-term anticoagulation for prevention of VTE recurrence.

Literature:

1 Barritt DW, Jordan SC: Anticoagulant drugs in the treatment of pulmonary embolism. A controlled trial. Lancet 1960; 1: 1309-12 2 Kearon C et al.: Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis. 9th ed.: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012; 141: e419S-96S 3 Gomez-Outes A et al.: Direct-acting oral anticoagulants: pharmacology, indications, management, and future perspectives. Eur J Haematol 2015; 95: 389-404 4 Schulman S et al.: Dabigatran versus warfarin in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 2342-52 5 EINSTEIN Investigators; Bauersachs R et al.: Oral rivaroxaban for symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 2499-510 6 EINSTEIN–PE Investigators; Büller HR et al.: Oral rivaroxaban for the treatment of symptomatic pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 1287-97 7 Agnelli G et al.: Oral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 799-808 8 Hokusai-VTE Investigators; Büller HR et al.: Edoxaban versus warfarin for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 1406-15 9 van Es N et al.: Direct oral anticoagulants compared with vitamin K antagonists for acute venous thromboembolism: evidence from phase 3 trials. Blood 2014; 124: 1968-75 10 Konstantinides SV et al.: 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J 2020; 41: 543-603 11 Stevens SM et al.: Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: second update of the CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 2021; 160: e545-608 12 Baglin T et al.: Incidence of recurrent venous thromboembolism in relation to clinical and thrombophilic risk factors: prospective cohort study. Lancet 2003; 362: 523-6 13 Kearon C et al.: Categorization of patients as having provoked or unprovoked venous thromboembolism: guidance from the SSC of ISTH. J Thromb Haemost 2016; 14: 1480-3 14 Rodger MA et al.: Validating the HERDOO2 rule to guide treatment duration for women with unprovoked venous thrombosis: multinational prospective cohort management study. BMJ 2017; 356: j1065 15 Kearon C et al.: A comparison of three months of anticoagulation with extended anticoagulation for a first episode of idiopathic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 901-7 16 Agnelli G et al.: Three months versus one year of oral anticoagulant therapy for idiopathic deep venous thrombosis. Warfarin Optimal Duration Italian Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med 2001; 345: 165-9 17 Couturaud F et al.: Six months vs extended oral anticoagulation after a first episode of pulmonary embolism: the PADIS-PE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015; 314: 31-40 18 Konstantinides SV et al.: 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 3033-69 19 Kearon C et al.: Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 2016; 149: 315-52 20 Agnelli G et al.: Apixaban for extended treatment of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 699-708 21 Weitz JI et al.: Rivaroxaban or aspirin for extended treatment of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 1211-22